Hugo Kunz

Content

Pictures

Annotations

Text

---

page +

Obviously Kunz describes Copiapó during the sharp economic downturn in the 1880s / 1890s (1880/90). He names as the only working mine in the Dulcinea sector (located near Carrera Pinto)

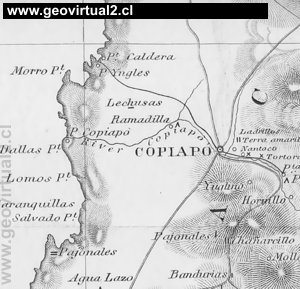

GILLISS, J.M. (1855)

Guía SudAmericana (1910-1912)

Guía SudAmericana (1910-1912)

Kunz (1890): Map of the naval lines in South America.

Literature: Copiapo at 1890

Hugo Kunz published a summary of

Copiapó's history in 1890 - a short description of the city in the

Atacama Desert.

Original text:

Page 414 - 416

The town of Copiapó, founded in 1772 by Jose Manzo

on the river of the same name, 396 metres above sea level and connected

by rail to the port of Caldera 82 kilometres away since December 1851,

is the centre of silver and copper mining in the province of Atacama.

The city is in pleasant contrast to Caldera, thanks to its location,

favoured by lush vegetation with its majestic churches, tasteful, partly

two-storey houses, its beautiful private gardens and statues adorned

with public squares, the impression of prosperity and a certain

elegance. The city has a beautifully built theater, a Lyceum, mining

academy. Gas lighting, there is a railway, post, telegraph station and

seat of an imperial German consulate.

Copiapó owes its world renown to the famous silver minerals of

Chañarcillo, discovered 10 miles away in 1832.

(...)

In addition, Copiapó has declined as a result of the decline of the

copper industry. Only an English owned copper mine (Dulcinea), near

Puquios, is still successfully mined.

(...)

At the beginning of the 1860s, Copiapó had three banking businesses in

Edwards, Ossa Escobar and Gormaz. The latter was soon liquidated. The

two remaining ones were then joined by one of only very ephemeral

duration, that of C. Lamarca, after whose departure in the province of

Atacama, more than other needy of financial institutions due to the

character of their industry, for two decades the banks of Edwards and

Escobar divided the money transactions among themselves. The copper

smelting works were (among others in Chañaral etc.) six larger ones in

the province: in Nantoco of Escobar, at Tierra Amarilla the owner

Edwards and the other four in Caldera. The number of silver refineries

(amalgamation works) was even greater, the majority of whose products

were taken over by the two banking businesses mentioned above.

Three of the copper smelting works in Caldera did not experience the

seventies. From that time onwards, the standstill and in some cases

setback in industry and commerce generally came to light, as can be seen

in the dividends of the Copiapó Railway, in which prosperity is fairly

faithfully reflected. The 12%, to which the same seemed to have been

standardized, shrunk worryingly, - and the fact that they still kept to

a certain extent can only be thanked for the fact that the maintenance

plant of the railway has become a rich source of income and merit by

taking over work for the public of the north.

In the 1880s, the province's prosperity was often referred to as a

tradition. The silk, which the two banks had spun in the past, was

coming to a close. It was no longer sufficient for two - at most for one

- of course for what, as they say, could last the longest. Thus it

happened that the Escobar' sche drew the flag and that the Edwards' sche

alone as a matador, in a way as an unrestricted ruler - because in

critical time runs the owner of the money monopoly, especially in

industrial districts, remained on the place.

This situation of things is to be put to an end now, not precisely

because a new, particularly noticeable upturn in the industry lying

below it has occurred and the field of activity for money institutes has

again expanded to such an extent that Edwards's would have become

materially inadequate for transport, but because the way in which the

latter has managed its monopoly seems to have made the same thing rather

unpopular.

The original texts were digitized, transformed to

ASCII and edited by Dr. Wolfgang Griem

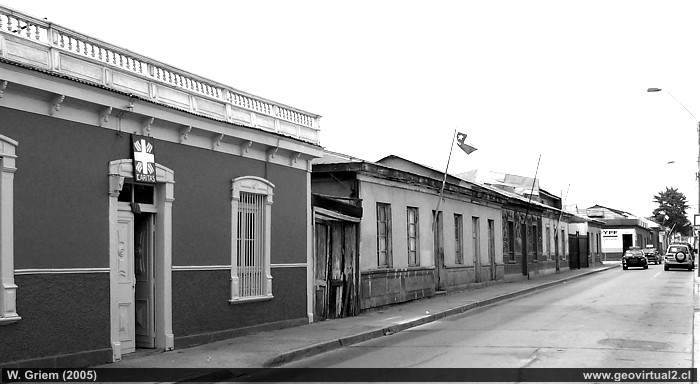

Street of Copiapó.

History of Atacama

Journey to Atacama

Entrada Copiapó

La Plaza (town square)

Hitos turísticos

Museo Mineralógico y

Regional

Cronología de Copiapó

Textos históricos de Copiapó

Darwin at Copiapó (1835)

I. Domeyko y Copiapó (1840)

Treutler en Copiapó (1853)

Treutler - Copiapó (1853)

Gilliss, Copiapó education (1853)

Philippi en Copiapó (1853)

Pérez Rosales Copiapó (1859)

Tornero Copiapó (1872)

Tornero Copiapó, aguas (1872)Tornero Copiapó,

datos

Tornero Edificios Públicos

Tornero Empresas en Copiapó

►

Hugo Kunz in Copiapó 1890

Enrique Espinoza - Copiapó

Ramírez, Copiapó 1932

Terremotos:

Burmeister: Terremoto (1859)

Imágenes del pasado: Copiapó

Copiapó hoy y Ayer

Hoteles -

Donde Comer

Mapas

Hugo Kunz

Libro: Chile y las colonias . .

Copiapó

Caldera

Chañarcillo

Ferrocarril de Copiapó

Ferrocarril trasandino

Trayecto Carrizal - Co. Blanco

Visitors of

Atacama

List

of Visitors

R.A. Philippi, Atacama

Paul Treutler

Charles Darwin

Ignacio Domeyko

Hugo Kunz

Kunz about Copiapó

Hugo Kunz en Chañarcillo

Atacama

Mining history of Atacama

The railroad history of Atacama

Cartas históricas de Atacama

Camino del Inca - Qhapaq Ñan

Smelter Inka

Pukará Punta Brava

Illustrations of Chile

El sector Copiapó

Viaje al valle interior

Paso San Francisco

Ruta a - Diego de Almagro

La Panamericana

más rutas de Atacama